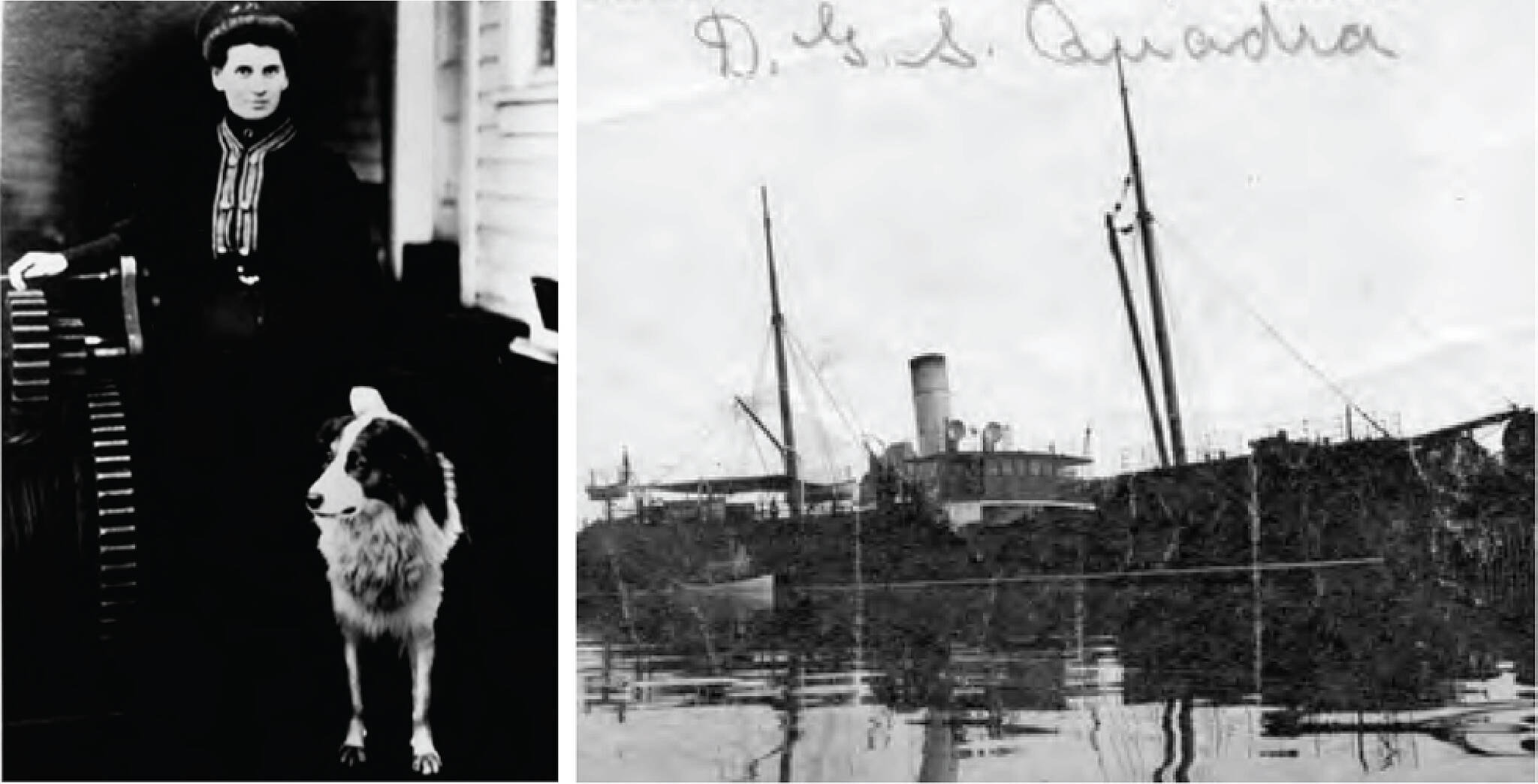

Minnie Paterson made headlines in 1906 for her heroic hike along what would become Vancouver Island’s West Coast Trail to raise a rescue for the men aboard the shipwrecked Coloma. This is an excerpt from Flourishing and Free: More Stories of Trailblazing Women of Vancouver Island by Haley Healey (Heritage House Publishing, 2021).

Minnie Paterson scanned the black nighttime rainforest, searching for the trail she lost among the darkness and heavy sheets of rain. She took in her surroundings by dim lantern light: tall sword ferns, leafless moss-covered tree branches, deep puddles of mud, and her black-and-white collie Yarrow dripping wet beside her. She needed to find the slash in a tree that marked the path, specifically a rough telegraph line trail that connected lighthouses. She was on a mission to save some shipwrecked sailors and was making her way from her lighthouse to the telegraph cabin down the coast.

She refused to let panic set in and held the lantern up in front of her, moving it around in a circle.

Everything was blurry through thick curtains of rain. She was immersed in a world of mud holes and fallen trees.

Far below her, she heard monstrous ocean waves pounding against reefs and cliffs. She took a few steps forward … and nearly tripped over a wire. Yes! The telegraph line would show her the way to the telegraph cabin. She felt her way along the wire until the lantern light revealed the expected slash on the tree. Back on the trail, she pushed onwards.

READ MORE: Vancouver Island’s West Coast Trail reopens in June

Earlier that evening, Minnie’s husband Tom, the lightkeeper at the Cape Beale lighthouse, noticed a ship at sea in obvious distress. Tom woke Minnie and they took turns watching the ship through a telescope while wind rattled the windows and walls of water crashed into the light tower.

Through the telescope, Minnie and Tom saw men clinging to the ship rigging while their ship got pummelled by waves. They saw fallen masts and an upside-down flag — the international signal for distress. What they didn’t know was that the lifeboats were trashed, and the men had tried, unsuccessfully, to construct a raft. What they did know was that the men were in trouble and their ship would be smashed to pieces into the ocean if someone didn’t help them. The ship was the Coloma and it had been sailing with lumber from Port Townsend to Australia.

Normally Tom and Minnie would help ships by telegraphing to Bamfield, the small village that lay eight kilometres away. Tonight though, the telegraph line was broken from the storm; the only hope of saving the men was getting word to the Quadra, a government steamer that normally carried out mail, supply, and fuel deliveries as well as law enforcement. The ship, under the command of Captain Charles Hackett, was docked off Bamfield Inlet — 10 kilometres away from their light station at Cape Beale.

Tom couldn’t leave the light and foghorn, so Minnie volunteered to go. She called their collie Yarrow, grabbed a lantern, and stepped out the door. If she got word to the Quadra, it could get to the stranded men — if she arrived before the floundering ship broke apart and the men drowned, that is.

Minnie’s first obstacle was crossing the sand neck that joined their light station to Vancouver Island. It was high tide, so she had to wade for 150 feet through frigid waistdeep water until she reached the telegraph trail.

Then her hike began.

She half ran, half walked through gale-force winds and thick rainforest.

READ MORE: A hiker’s guide to Vancouver Island’s Cape Scott Trail

The trail was not well marked — and not much of a trail most of the time. The storm had taken down branches and turned the area into more of a pond than a forest. Minnie lost the trail and found it again several times, sometimes gripping the telegraph line to find her way. The trail Minnie hiked on that night — though knee-deep mud and torrential rain — was what is now (Vancouver Island’s) famous West Coast Trail.

Minnie desperately wanted to arrive safely at the Quadra. She had to. Her five children back home needed her.

Hours later and after much wet, cold, hard exertion, Minnie finally arrived at Bamfield Inlet. But the rowboat that was usually there to row to the Quadra was not there: Her journey was not over yet. She had to go another few kilometres, she was determined to make it to the telegraph cabin.

Shattered with exhaustion, Minnie at last dragged herself up the steps to the linesman’s house. The linesman’s wife, Annie McKay, answered the door. She quickly told Minnie that her husband was out fixing the telegraph line. Minnie relayed the situation of the shipwreck to Annie, and together, they got in a small skiff and rowed through the angry sea toward the Quadra, taking turns to bail the rain out of the boat. They arrived at the Quadra and quickly informed Captain Hackett about the shipwreck off Cape Beale.

He set off immediately at full steam toward it while Minnie and Annie rowed back to shore. The fates of the stranded sailors now lay in the hands of Captain Hackett. Minnie’s message was delivered, her mission complete.

A week later, when telegraph lines had been repaired, Minnie discovered her harrowing journey had been worth it: the Quadra had made it to the shipwrecked sailors just in time, just moments before their ship smashed into the jagged sharp reef.

All 10 sailors on board had been rescued.

Minnie’s story is one of courage, bravery and dedication. She is remembered as a heroine who hiked near the famous West Coast Trail before it was a lifesaving trail for shipwrecked sailors or the recreational hiking route we know today. Minnie’s name and legacy live on from her epic hike, which earned her international fame, in the form of the many sailors whose lives she saved.

This excerpt is reprinted from SOAR magazine, the in-flight magazine for Pacific Coastal Airlines.

Love the outdoors? Join a rod & gun club!

Love the outdoors? Join a rod & gun club!