In the Royal BC Museum’s new Dinosaurs of BC travelling exhibition, visitors can use an interactive video series to tag along with Curator of Palaeontology Dr. Victoria Arbour as she hunts for dinosaur fossils in northern B.C.’s Spatsizi Plateau.

Touch the screen to watch the first video, where Dr. Arbour and her colleagues admit that they haven’t found anything yet — then share in their excitement as they record their first fossil find. In the second video, watch Dr. Thomas Cullen hoist a grey rock with a distinctive white streak, and listen to Dr. Arbour and Dr. Cullen making their first guesses at what type of bone it might be.

Turn your back to the museum’s video screen and you’ll find some familiar rocks behind glass — the very fossils discovered in the field footage. It’s a thrill to connect the dots between screen and real life, and it opens the door to participating in the scientific process. What kind of bone do you think it is? If you noticed similar markings on a rock on your favourite hiking trail, would you think it was a million-year-old fossil?

The truth is, palaeontologists often don’t know what they’re looking at either — at least not at first. In the field they collect potential fossils, record observations and carefully package findings. Back in the lab they examine things more closely, comparing them to other fossils and developing more specific identification, sometimes over years.

That’s what happened with Dr. Arbour’s friend Buster, whose full name is Ferrisaurus sustutensis. Buster first came into Dr. Arbour’s life as a collection of bones in a shoebox, donated to the University of Dalhousie after geologist Kenny Larson found them in northern B.C. She studied the bones for her undergraduate honours thesis, discovered that they were among the first dinosaur bones found in B.C., then returned to the bones over a decade later with more knowledge and skill. She and Dr. David Evans were able to identify Buster as a small relative of dinosaurs like triceratops, and a few years later, they discovered that Buster was actually a species new to science.

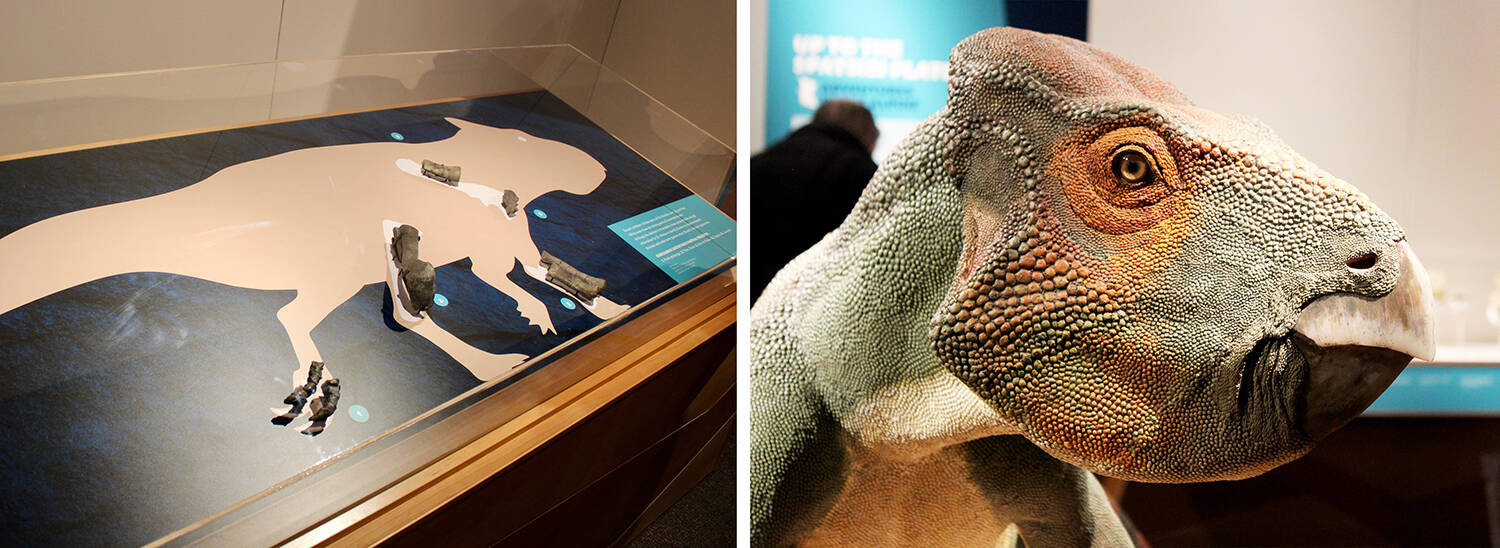

In the Royal BC Museum exhibit, showing in Victoria through Jan. 7, 2024, you’ll get to see that shoebox of bones (helpfully displayed on a silhouette of Buster’s approximate shape). You’ll also get to see a life-size sculpture of Buster created by paleoartist Brian Cooley, which Dr. Arbour says is one of the best dinosaur reconstructions she’s seen.

With just a few bones to spark your imagination, you’d be forgiven for picturing Buster’s body differently than Cooley’s creation. We haven’t found any preserved soft tissue of Buster’s species (yet), but Cooley, Dr. Arbour and other scientists use a variety of clues to hone visualizations.

“Everything that you see in this Buster model is based on either direct evidence (like, say, the proportions of his feet), or we look at the next-closest relatives, or we go a little bit further out and look at the big picture of dinosaurs,” Dr. Arbour says.

“Even in doing the colour, we look at modern animals that we think might have had similar behaviours. This is an animal that’s living in a forested environment. It’s small, so it’s probably going to rely at least a bit on camouflage, so having mottled green scales makes a lot of sense. But Buster also has this little bit of a frill and deep jaws, and lots of reptiles get colourful in that area during mating season, so he can have a little bit of colour. Maybe this is a ‘mating season Buster’ with his little ‘show-off stripes’ on his face.”

If you build an image of Buster based on what you know of his environment or similar species, you’re beginning the work of palaeontology.

Finding fossils in B.C.

Alberta, Montana and New Mexico are well known dinosaur hotspots in North America, but that’s not the only place dinosaurs lived — it’s just where fossils are particularly easy to find.

“In Alberta, fossils have been collected for well over 100 years by many people. In many ways we’re still in the very early phases of exploration in British Columbia — it’s only been in about the last 20 years, with a much smaller crew of people doing this kind of work,” Dr. Arbour says. “We also face some unique challenges in British Columbia, because of our very forested, extremely mountainous terrain.”

Palaeontologists hunt for fossils in the field as much as time, funding and B.C.’s extreme backcountry will allow, but many discoveries are also made by amateurs with a keen eye. Fossils are protected by law in BC, so those who find fossils are encouraged to document their findings and report them to Dr. Arbour.

- READ MORE: Courtenay fossil hunter finds ancient turtle on local river

- READ MORE: Extreme hiking, time travel and science converge in the Burgess Shale

The Victoria Palaeontology Society, Vancouver Island Paleontological Society (based in Courtenay) and Vancouver Paleontological Society organize field trips and events for amateur fossil hunters, and have strong relationships with the Royal BC Museum. In Tumbler Ridge, one of the most notable discoveries is a trail of dinosaur footprints discovered by local children Mark Turner and Daniel Helm, who were walking the bank of Flatbed Creek after playing in the rapids on inner tubes.

“There are literally fossils all across B.C., not just from dinosaurs but also things like trilobites and plant fossils. Because we have such complicated geology in B.C., you can probably find something almost anywhere you go,” Dr. Arbour says.

Key ingredients in every fossil discovery:

- Search environments where the animal lived. Future fossil hunters won’t find fossils of elephants in North America because this isn’t the right habitat for them (except in zoos), and the same rules apply to prehistoric species.

- An animal will only be preserved if the right conditions are present when it dies. Many fossils are found along rivers, oceans and valley floors, because it’s easier for things to get buried and preserved in those conditions. If an animal is eaten by a predator or scavenged, or if it’s broken down during fossilization by environmental factors, it won’t be preserved in the fossil record.

- The fossil needs to come back to the surface, in a place that humans can access today. “That’s why badlands and deserts are so good for fossil hunting, because there are no trees covering up the rocks. Part of our challenge in B.C. is that a lot of it is forest, so we just don’t see the rocks. That’s why we go up into the mountains or along rivers,” Dr. Arbour says. There may be fossils deep underground that haven’t been uplifted yet, and fossils can also be discovered while digging for resources (the Royal BC Museum exhibit includes a model of footprints found on the wall of a coal mine in southeast B.C.’s Elk Valley).

- Luck. Many fossils are discovered by chance, so keep your eyes peeled! Once one discovery is made, scientists will often scour the area looking for more fossils, assuming they’re able to gather enough funding to finance the expedition.

The more you know about fossils, the easier it will be to spot them. Books like West Coast Fossils: A Guide to the Ancient Life of Vancouver Island are a great place to start, as well as the Royal BC Museum’s exhibit.

If you go:

- Dinosaurs of BC is showing at the Royal BC Museum in Victoria through Jan. 7, 2024. Entry is included with general museum admission.

- Plan your visit at royalbcmuseum.bc.ca

A ‘150-acre wonderland of forest and flowers’ awaits on Bainbridge Island

A ‘150-acre wonderland of forest and flowers’ awaits on Bainbridge Island