When the subject of the Second World War comes up, travel-minded history buffs usually think of sites in Europe or the UK. As a Canadian, if you’re anything like me, and history and travel are inseparable bedfellows, your thoughts don’t turn immediately to the shores of British Columbia as a prime choice.

Travelling the West Coast: How the Second World War came to our shores

Growing up in Victoria, I was aware of the defences at Fort Rodd Hill in Colwood, just outside Victoria, and the military observation post at Gonzales Hill in Oak Bay, but the war was as distant in time as it was in miles until I did a little digging.

Part of the fun of historically based travel is to go to the actual place where something momentous happened, and I was pleasantly surprised to find that my interest in all things Second World War could be nourished here in B.C.

Not only did Canada have defences up and down its vast Pacific coastline, including barbed-wire on the beaches and pilings to prevent landings, just like Europe, it actually came under attack.

Or did it?

1. A shot over the bow or an engineered plot?

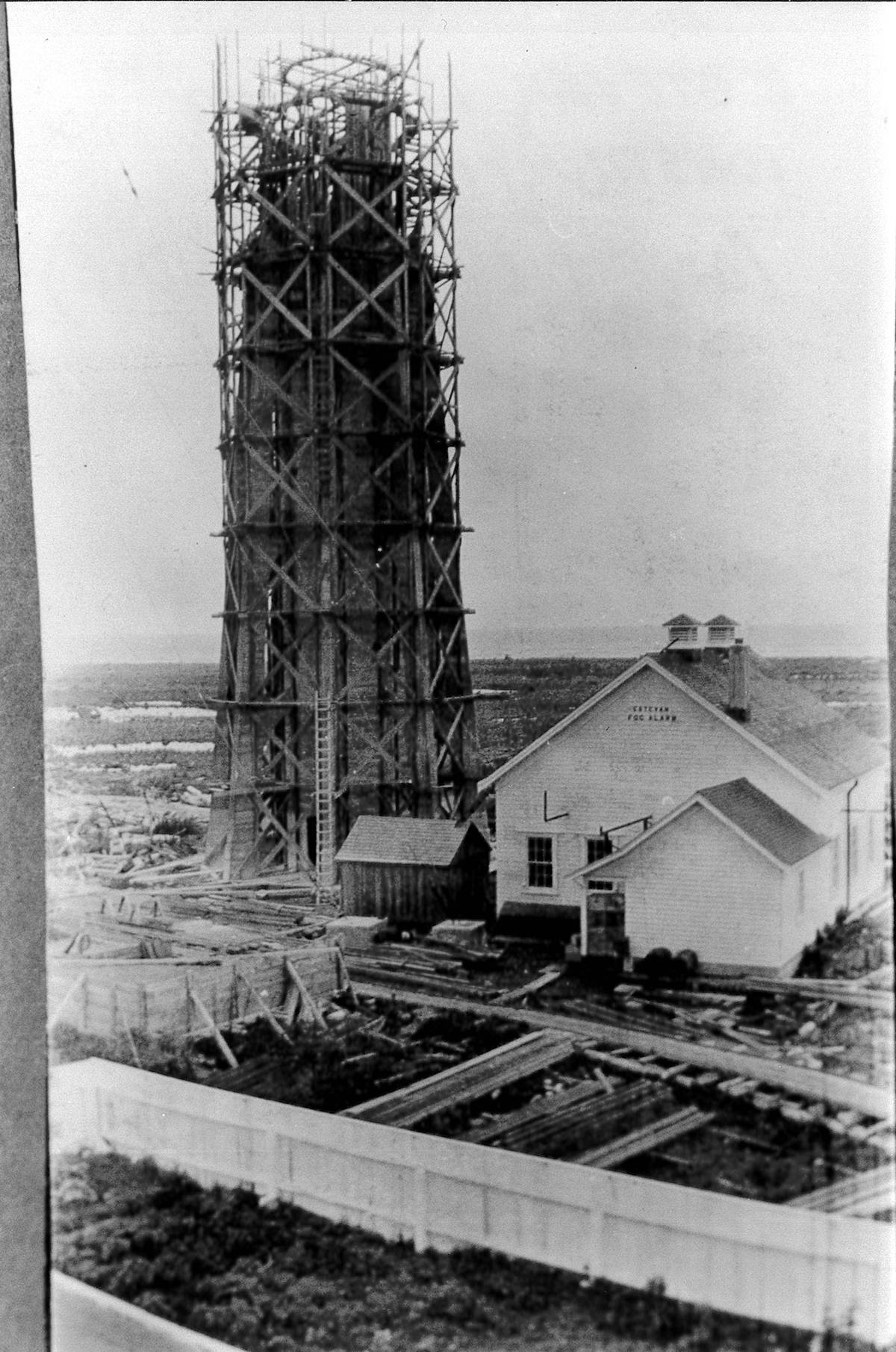

Estevan Point Lighthouse, on the Island’s central west coast, played an important role in the coast’s brush with modern warfare and in changing the public’s minds on Canada’s role. Accessing this historically significant spot is not for the faint of heart but it allows those who visit to see some of the most pristine areas of coastline imaginable while also seeing the site of the only Second World War bombardment on Canada’s soil.

Named after Esteban Jose Martinez, second lieutenant of Lieut.-Comm. Juan Perez of the Santiago, the first European to sail here in 1774, the lighthouse suffered the first attack on Canadian soil since the war of 1812.

Early in the Second World War, as the war in the Pacific ramped up, the threat of Japanese invasion was taken seriously by the Canadian government, especially after the Dec. 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor.

On a dark night, June 20, 1942, the remote Estevan lighthouse was attacked by a single Japanese submarine, I-26, as the official line says. It seems more than likely that the intended target was not the lighthouse at all, but the nearby radar base.

Differing versions?

Estevan Island lightkeeper Robert Mike Lally’s version conflicted with the official line, describing a large surface vessel, a submarine and a small boat. According to the official operational historical work on the subject, No Higher Purpose: The Official Operational History of the Royal Canadian Navy in the Second World War, 1939-1943, “Lally later claimed that two ships were firing but, like other reports that an aircraft was flying overhead during the bombardment, this proved without foundation” (356).

Lally was a First World War veteran and likely all-too familiar with the sound of shells. That night, two-dozen shells, give-or-take, rained down, but not one hit the target. Robert Lally Jr., out fishing, also described a large surface vessel but, it should be noted, even trained naval experts make errors in identifying ships. Lally logged his account, and the page was taken during the official investigation and “mysteriously disappeared,” a story that adds fuel to the fire for conspiracy theorists.

Other eye-witness accounts, including one from local homesteader Cougar Annie, also differed or agreed with the official line. Under pressure and taken by surprise, it’s not unusual for widely varying accounts of a single event.

Perhaps most compelling evidence is the post-war confirmation that the attack by a single Japanese sub, I-26, is supported by official Japanese documents and the captain of the submarine, Commander Yokata.

What really happened? Conspiracies controversy, and conscription

One controversial theory suggests it was an engineered event, meant to convince Canadians to accept conscription. Conscription was a make-or-break topic for Mackenzie King’s wartime government, and something that Mackenzie King adamantly opposed. Donald Graham, a historian and lightkeeper, controversially suggests that King conspired with the U.S. to stage a Pearl Harbor-type attack on a smaller scale, to scare Canadians into accepting conscription, which seems in direct conflict with Mackenzie King’s own views and the timeline of actual events.

Whatever the truth, the attack took away the feeling of a relative remoteness from the conflict. It was too close to home. Mackenzie King wrote in his diary that Estevan “station had been shelled last night… clear evidence of a Japanese attack upon the shores of Canada… also torpedoing of other ships off the Pacific Coast and rescue of passengers. It seemed to me that these events could not but have their affect on Canadian feeling with regard to conscripting men to be sent over seas to Europe which is, of course, all that the conscriptionists are really concerned about, and to win their point regardless of the effect on Canada itself.”

Looking at the timeline of events, April of 1942 had already seen a plebiscite on the subject of conscription, in which the Canadian public had voted to allow it, although Mackenzie King was extremely reluctant. The shelling on the lighthouse in June of 42 came after that event and had no influence on that vote. In any event, Mackenzie King’s government did not actively conscript soldiers until 1944!

As fun as it is to imply a conspiracy, the facts suggest a much different story.

Hike into history

If you can make the hike, it’s well worth a look to see just how remote this spot is, and of course to take in the beauty of the rugged coast. It’s hard to imagine shells raining down!

It does prompt one to wonder why this spot? It’s not like it was heavily populated, and still isn’t. Why not Victoria or Vancouver, or Nanaimo? It seems a peculiar choice until you realize that the Japanese often launched a salvo and then disappeared — it was an act repeated up and down the coast. It is also true that Victoria was more heavily defended and this was a softer target. Whatever the reason, it’s a fascinating little piece of history!

Along the way, you can visit Cougar Annie’s Gardens, Hesquiat Village, and enjoy the pristine wilderness.

For those who don’t fancy such an intrepid journey, the original light from the station currently marks the location of the far-more-accesible Sooke Museum. The lenses still bear the scars of the attack.

How to get there: To get to the trailhead, take a float plane or charter boat from Tofino. Camping gear and outdoor backwoods experience are necessities for this expedition. Plan ahead, plan for rain, have good footwear and ensure that you carry everything you will need, including water or a water purifier. Be aware of bears, and carry bear spray. This 50km hike is mostly coastal, and is one of the least travelled paths on Vancouver Island, attracting only about 100 hikers per year.

READ MORE: Disaster and response: The Valencia Tragedy and the West Coast Trail, Part 1 of 2

READ MORE: Victoria museum exhibit dives into shipwreck’s ‘Theatre of Horror’

2. The Bomber Trail: A living relic, but no ghosts

If you want something a little less arduous with Second World War connections, and less controversial too, this hike is just the ticket.

As the war progressed, and especially after Pearl Harbor, construction of the airfields at Tofino and Ucluelet and the Radar Hill base (also worth a look!) picked up to deal with potential airstrikes. None came, but they did have to deal with incendiary bombs attached to high-altitude balloons which were launched by the Japanese between December 1944 and March 1945. They fell along the west coast of North America and as far inland as Manitoba. There were no casualties in Canada and only one in the States.

Explosive situation

Wartime activities are not confined to combat, and on Feb. 10, 1945 a Royal Canadian Air Force Consolidated PBY-5A Canso, of the flying-boat variety, piloted by Air Force Pilot Ron Scholes with his 11 crew, took off on a training flight at 23:00 hours. Shortly after take off, the newly repaired port engine failed.

The plane began to clip the tops of the trees. The quick-thinking pilot stalled the plane to slow its descent, a maneuver which saved all souls as the cargo was a half ton of explosives. The bomber remains where it came to rest on a slope below Radar Hill.

Fortunately, this is not a tragic tale and the only injuries were a few broken bones, scrapes and bruises.

The crash site, accessible by a moderate-and-often-muddy trail, is weirdly haunting. My first feeling upon seeing it was relief that all hands survived. My second was that it was a miracle. The plane appears suspended in the trees, sort of hanging above you as you approach. It’s a poignant reminder of those who took great risks to preserve freedom, even away from enemy lines.

The wreckage was considered irretrievable at the time, and was stripped by the military a few days after the crash. Today, it has been tagged with graffiti, and parts removed by military collectors. What to do with the plane and/or its resting place remains a subject of debate nearly 80 years after she came to rest. Read about other Second World War plane crashes here.

How to get there: Find a map link to trail location here.

READ MORE: Evidence of WWII’s impacts on Tofino and Ucluelet remains 75 years after D-Day

For more on Tofino and where to stay, check out Tourism Tofino. Many local hotels are available in Tofino, as well as camping.

As always, check with the local communities to make sure travel is allowed and take any COVID-19 restrictions into account when planning your trip.

Plan your adventures throughout the West Coast at westcoasttraveller.com and follow us on Facebook and Instagram @thewestcoasttraveller. And for the top West Coast Travel stories of the week delivered right to your inbox, sign up for our weekly Armchair Traveller newsletter!

Set sail for a close-to-shore Sidney Spit escape

Set sail for a close-to-shore Sidney Spit escape