Sid Grauman was a teenage Klondike stampeder who sold newspapers in Dawson City during the gold rush. Years later, he opened several lavish movie theatres in Los Angeles, including the Egyptian, the Million Dollar and the Chinese. He was a master of publicity, and many major cinematic productions were premiered in flashy events in his theatres during the 1920s and ’30s. Each was accompanied by a prologue — an extravagant live production employing a full orchestra, ornate stage sets and large cast.

Charlie Chaplin’s movie The Gold Rush has a scene in which Chaplin, portraying a starving tramp, chows down on his shoes. It is possible that the story was inspired by Grauman’s skillful retelling of the story of Yukon’s Bishop Isaac Stringer, who became known as “The Bishop Who Ate His Boots.” The Chaplin film premiered in Grauman’s Egyptian Theatre on June 26, 1925, following heavy promotion during the days leading up to the opening night.

When the celebrities began to arrive at 8:30 p.m., their names were announced over a public address system. Among those who attended were the elite of Hollywood: Chaplin was there, as were Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford. Sam Goldwyn and his wife strode up the red carpet, followed by Louis B. Mayer. Other Hollywood luminaries made their appearance: Marion Davies, William S. Hart, Cecil B. DeMille, Hoot Gibson, Mae Murray and Rudolph Valentino. Comic screen stars Buster Keaton and Roscoe Arbuckle (who had performed in the Auditorium Theatre – now the Palace Grand – in Dawson City 19 years earlier) were there too.

The press pointed out that Sid Grauman had drawn upon his personal experiences in Dawson City to design the elaborate stage setting of the Monte Carlo dance hall for the prologue, in which 100 people performed on the stage. The prologue, titled “Charlie Chaplin’s Dream,” was reported to be at least as interesting for the nearly 2,000 patrons as the film itself. It included an ice-skating ballet, the balloon dancer Lillian Powell and a “stunning dance hall set” for the finale. As for the movie, it is considered by many to be Chaplin’s best work, and the one for which he most wanted to be remembered.

The works of Robert Service also appeared on screen during the 1920s. The Law of the Yukon, based upon Service’s poem of the same name, was released in 1920. Directed by Charles Miller and starring June Elvidge and Edward Earle, it was set in a saloon in the Yukon and includes a healthy dose of romance.

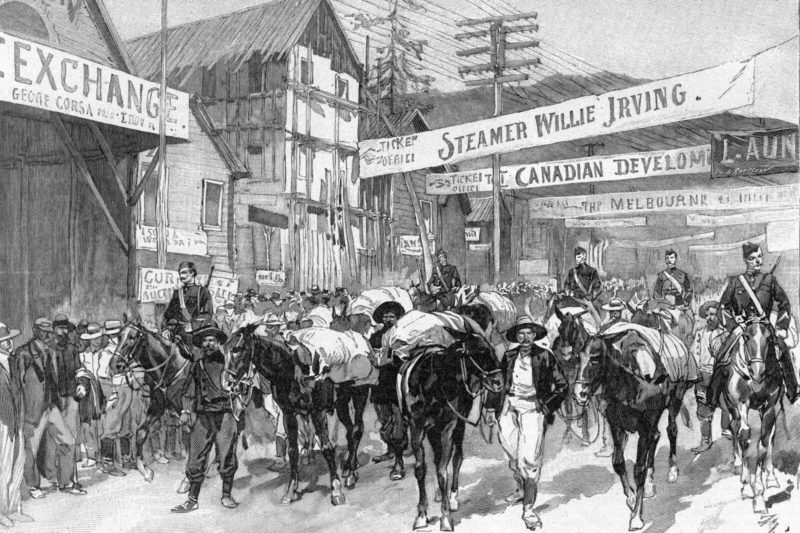

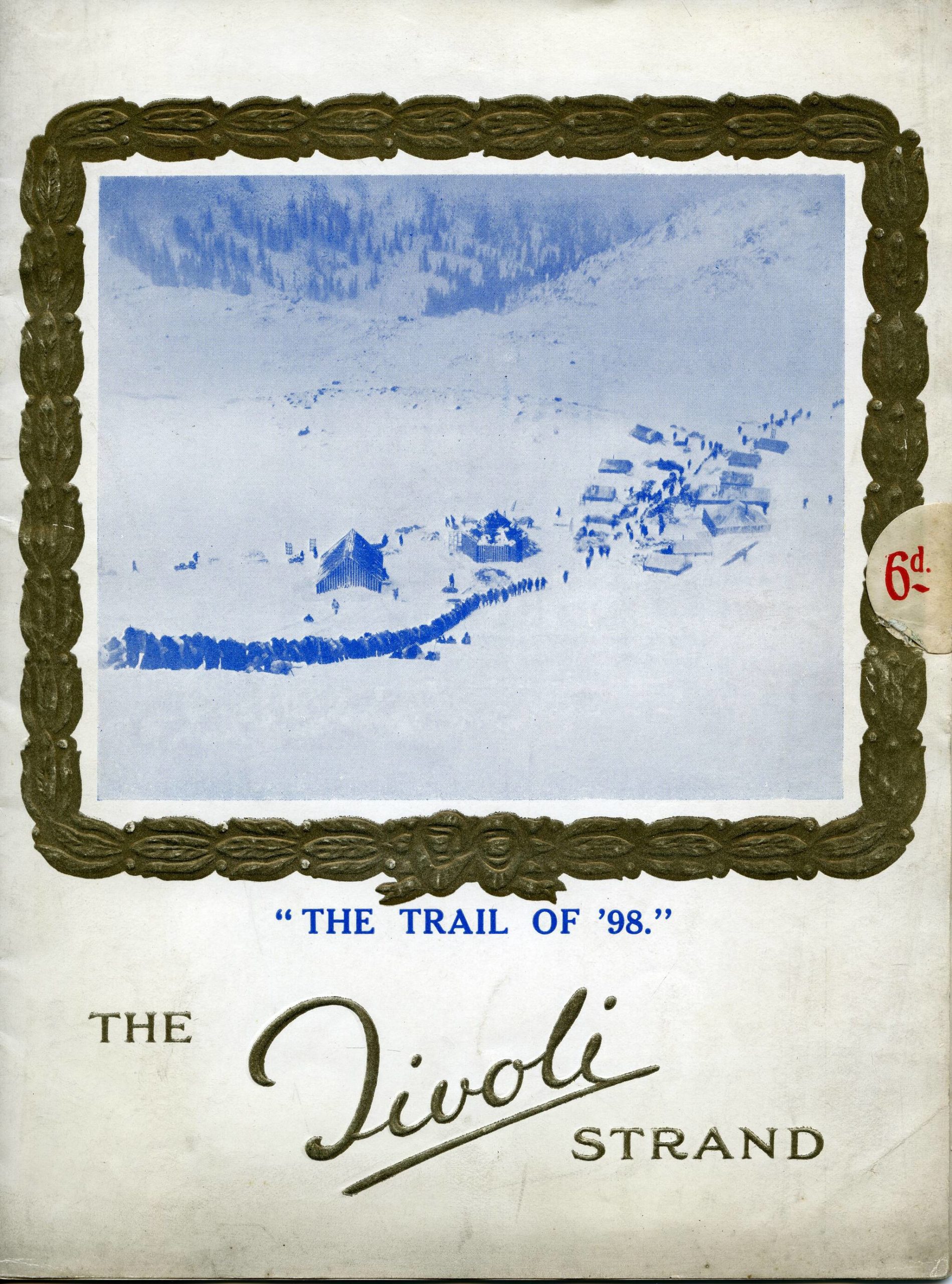

A more ambitious film was the 1928 release of The Trail of ’98, based upon Robert Service’s first novel, for which a film crew had been sent to the Yukon the year before to gather footage. The film opened to much acclaim and was proclaimed an immense hit when it premiered in the Astor Theatre in New York in March 1928. Sid Grauman secured the rights to open the film in Los Angeles in early May in his Chinese Theatre.

The opening was covered live on radio. A large spotlight projecting a shaft of light into the sky was said to be visible for 160 kilometres. A dance hall and bar were the backdrop for Grauman’s usual prologue, featuring a cowboy tenor, a harmony octet, a dancing waiter, a comedian and, and a famous Italian baritone. As the prologue concluded, half of the dance hall stage set wheeled to the left and half to the right, to reveal the screen.

The film heralded the end of the silent era in motion pictures. After the last night of The Trail of ’98, the theatre was closed until Aug. 3 to prepare for the transition to talkies and the first screening of the new MGM sound motion picture White Shadows in the South Seas.

In January 1942, Kate Rockwell-Matson rolled into Hollywood to consult on the making of a movie based upon her life story. The afternoon of Jan. 22, she sat in an office at Columbia Studios giving a demonstration of how to roll your own cigarettes. She pulled out a package of Bull Durham tobacco and tapped a little onto a cigarette paper that she held in one hand while simultaneously tugging with her teeth at the drawstring on the bag of tobacco in her other hand.

She did the same thing at the movie studio, giving instructions to actresses Jinx Falkenburg, Shirley Patterson and Evelyn Keyes. Falkenburg was reported to have been a quick learner.

“There’s hardly a man, woman or child who hasn’t heard of the colourful Klondike Kate, so her personally supervised story should have a ready-made audience,” stated American movie columnist Louella Parsons when she heard of Kate’s impending visit to Los Angeles. Parsons interviewed Rockwell when the latter arrived in Tinseltown. Kate gave the columnist a lesson in geography, pointing out that Dawson City was in Canada, as were the Mounted Police.

Being a veteran of the gold rush, Kate was a stickler for authenticity. The Hollywood dance hall girls weren’t anything like the real version, she was quick to note. “We danced like ladies — square dances and waltzes and things like that,” she said, “and our costumes were not the low-cut sort you see now. On stage we wore tights. Dance hall girls in those days wore high-necked shirtwaists, high button shoes and skirts down to the ground as well as wrist-length sleeves.”

Rockwell took pains to clarify that the Klondike wasn’t like the wild west. “People get funny ideas,” she said. “They think those days were wild and woolly for a fact. It was wild country all right, but the Mounties didn’t let much go wrong. As for the girls, I never heard a girl in a dance hall tell a vulgar story, swear, or curse … The scenes you saw in Dawson’s dance halls weren’t any wilder than what you see in some of the taxi-dance places today.”

But Hollywood and reality seldom overlap. The story that Columbia finally settled on was entirely fictional. “I don’t recognize anything in it that happened to me,” she said during the filming of the picture. Ann Savage, the actress selected to play Kate in the movie, did not wear lighted candles in her hair in the film, like Rockwell claimed to have done on New Year’s Eve of 1900. The film was never screened in Dawson City.

Like it or not, there are two facts about which one cannot argue. The first is that the Klondike gold rush had a mystique that inspired many Hollywood productions over the last century. The second is that accurate or not, Hollywood’s portrayal of the Klondike has played a major role in shaping the world’s perception of the Canadian North.

Michael Gates is Yukon’s first Story Laureate. His latest, “Dublin Gulch: A History of the Eagle Gold Mine,” received the Axiom Business Book Award silver medal for corporate history. His next book, “From the Klondike to Hollywood,” is due for release in September. You can contact him at msgates@northwestel.net

Edmonton’s River Valley moves closer to becoming an urban national park

Edmonton’s River Valley moves closer to becoming an urban national park