What is an ‘easy’ hike? For a mountaineer, an easy hike might be one that doesn’t require supplemental oxygen. For a parent with a stroller, even a single rail tie step can change an ‘easy’ hike to difficult. ‘Easy’ is in the eye of the hiker, so one of the best ways to gauge a trail you’ve never tried is to understand its characteristics. Then you can decide for yourself how it’s likely to drain your energy.

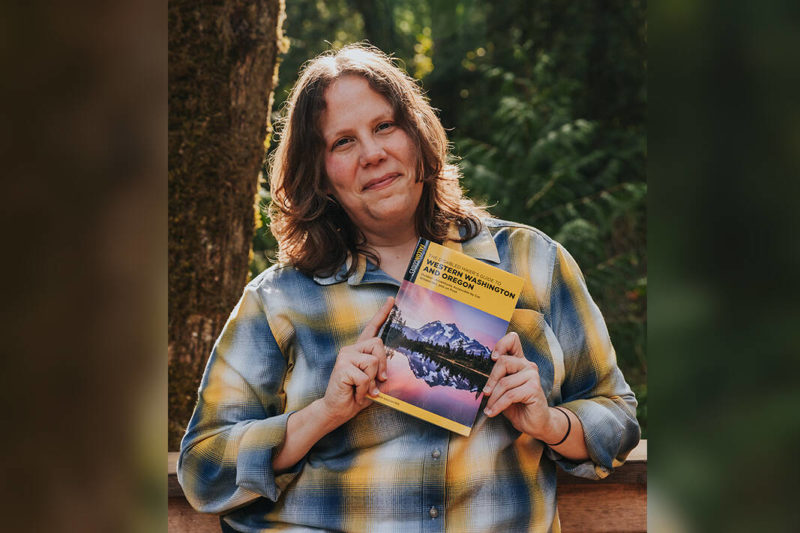

That’s the idea behind a new series of hiking guidebooks in the Pacific Northwest by Syren Nagakyrie, founder of Disabled Hikers.

A spoonful of energy

Among people living with disabilities and chronic illnesses, The Spoon Theory by Christine Miserandino is a popular method for describing the careful management that’s necessary when rationing limited energy. Miserandino, who has Lupus, uses spoons to represent units of energy: she starts the day with about a dozen spoons and then ‘spends’ them throughout the day on everything from visiting friends to cooking dinner. There aren’t enough spoons to do everything, but with careful planning she’s able to have a lot of good days.

READ MORE: Washington hiking guide offers a new way to find accessible trails

When Nagakyrie was writing their first guidebook, The Disabled Hiker’s Guide to Western Washington and Oregon, they decided to honour The Spoon Theory with the spoon rating system.

“I wanted to create a system that grew on our culture,” Nagakyrie says.

The spoon rating system helps readers understand how much effort a trail might take. Any one factor, including accessibility, difficulty and quality can shift the spoon rating. A long, flat trail may have the same rating as a short steep trail. Conditions like trail surface, width and cross-slope can effect the amount of energy you spend, too.

The point of the Spoon Rating System isn’t to declare, definitively, how hard or easy a trail might be. Every hiker has different abilities and needs. The Spoon Rating, along with other descriptions in Nagakyrie’s guidebook, empower all of us to decide for ourselves whether a trail meets our needs.

The Disabled Hiker’s Guide to Western Washington and Oregon was an instant success (it sold out immediately, and is now back in stock), and Nagakyrie is now working on a similar guidebook for Northern California. That means they’re currently doing a lot of hiking — on trails that don’t have clear accessibility descriptions.

“So much of my work has been having to create the thing I need to exist, so that I can create the thing,” they say with a smile.

READ MORE: Free beach wheelchairs create opportunity Victoria couple thought gone forever

Without guidebooks like Nagakyrie’s, hikers have to comb through online reviews and forums, park websites and other information to make a best guess at whether a hike will be accessible to their needs. Then they may arrive at the trailhead and find that a boardwalk trail begins with a set of stairs, making it inaccessible to some wheelchair users, or a trail marked as ‘easy’ lacks benches and places to rest.

“I spend countless hours researching every single trail. I’d guess that about 30 to 50 percent of the trails I attempt, I have to abandon before finishing because there’s some sort of access issue. Then maybe about half of the trails I complete are good for the guidebook.”

Nagakyrie grew up with multiple disabilities and chronic illnesses, including Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome and Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome. They also live with depression, anxiety and CPTSD. They estimate they’ll do about 200 hikes in order to find the 50 or 60 that will make it into the book, which is a lot to ask of any hiker.

But it’s not always a slog. They also get a great excuse to spend time outdoors.

“There is ample evidence that interacting with nature provides a range of benefits, including physical and emotional well-being and a sense of belonging. And yet the people who need these benefits the most — those who are disabled or chronically ill — face the most barriers to accessing the outdoors,” they wrote in their capacity as an Eddie Bauer One Outside Guide.

Nagakyrie’s appreciation for nature began when they were a kid, in their family’s yard.

“I wasn’t able to do a lot of the same activities my peers were doing, so I spent a lot of time hanging out in my yard. That instilled in me a sense of connection and belonging in nature early on,” they say. “In my 20s I started considering hiking, so I had to figure out what that meant for me and my body.”

Eventually they enrolled in an herbal studies program, which was their first introduction to group hiking. Before long they’d started a hiking group of their own: Disabled Hikers.

“We get a broad variety of people representing all types of disability. For a lot of them it’s often the first time they’ve done a group hike, and the first time they’ve done a group hike with folks who understand where they’re coming from.”

The decision to focus on Northern California for the next guidebook was based partly on need and partly on availability — it’s an area where folks in the disability community have expressed a need for more information, and also an area where trail organizations are improving their accessibility infrastructure. It’s also in Nagakyrie’s neck of the woods.

So what does it take for a hike to make the cut in one of Nagakyrie’s guidebooks?

“I love interpretive signage that teaches me more about the area,” they say. “I also like hikes that offer a really rewarding experience for the effort. A hike can be slightly difficult, but if there’s something really unique or incredible to experience, that can make it worth it.”

Plan your adventures throughout the West Coast at westcoasttraveller.com and follow us on Facebook and Instagram @thewestcoasttraveller. And for the top West Coast Travel stories of the week delivered right to your inbox, sign up for our weekly Armchair Traveller newsletter!

–

‘It was a super cool experience’: Wolfpack spotted hanging out in Kelowna

‘It was a super cool experience’: Wolfpack spotted hanging out in Kelowna