The last person to see a grizzly bear in Washington’s North Cascades left no trace.

Or so it seemed.

Countless articles describe how a biologist submitted the confirmed grizzly bear sighting in the region in 1996, after seeing a grizzly on the south side of Glacier Peak. He is always unnamed — a mystery to everyone, including the man himself.

“What a surprise,” said Canadian researcher Paul Paquet, who learned he was that biologist this week, when a reporter from Everett’s Daily Herald called him for an interview. “I seem to remember that I did report it, because I thought it was an interesting observation that might be useful.”

Paquet was hiking along the Pacific Crest Trail in Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest when he saw a female grizzly gorging on huckleberries about 55 yards away. He wasn’t afraid, having observed grizzlies and black bears before. After she left, Paquet checked to make sure the tracks matched those of a grizzly.

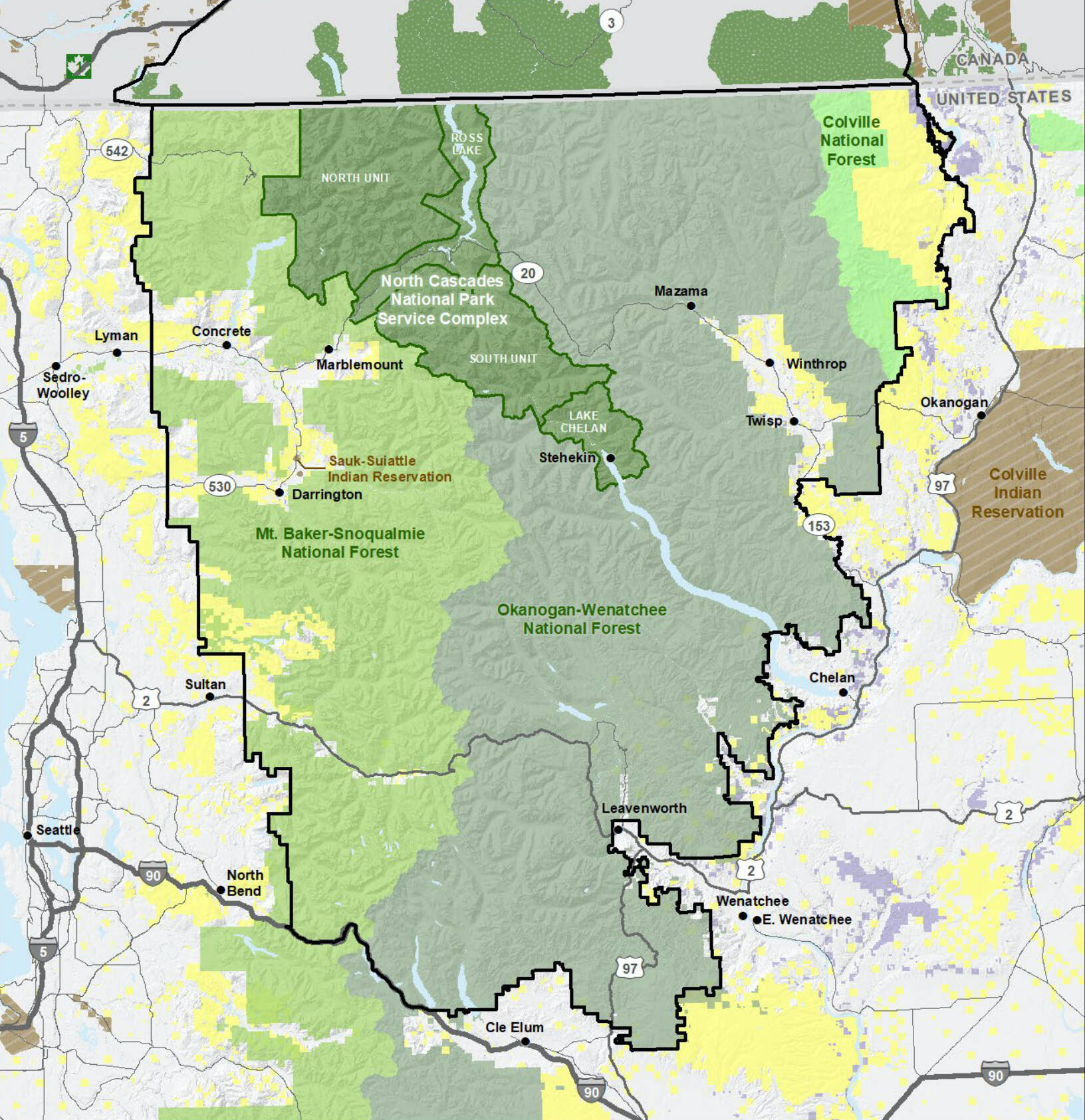

Now, grizzlies are considered extinct in the North Cascades, a region encompassing about 9,800 square miles in north-central Washington. The greater North Cascades extend into British Columbia, providing another 3,800 square miles of potential grizzly habitat. Roughly 15,000 grizzlies live there, but it’s unlikely enough of those bears will ever travel south of the border and regain a foothold in the wilderness.

But almost three decades after Paquet’s sighting, grizzlies now may be on the cusp of returning to Washington.

Last month, the National Park Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced their preferred option for grizzly bear reintroduction, with the goal of about 200 bears on the U.S. side of the North Cascades in the next century.

Under their ideal plan, federal officials would release three to seven bears each year — flown in by helicopter or dropped off by truck — to achieve an initial population of 25 bears within 10 years. The re-established population would also have special protection under Endangered Species Act, which allows wildlife and land managers, as well as local communities, more flexibility in removing or relocating bears that are involved in conflicts.

Federal agencies are expected to announce their final decision on the proposal in the weeks ahead. Wildlife experts and residents, however, still disagree on whether the grizzlies would be a welcome neighbor.

Bears chosen for the plan will likely be taken from Montana or Wyoming and captured in culvert traps. The bears will likely be released in a northern portion of North Cascades National Park, the southern unit of the national park that extends into the eastern edge of Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest, or a northern section of the remote Pasayten Wilderness — where the bears once roamed.

Of all the people to verify a sighting of the apex predator, Paquet is surely qualified. He has served on grizzly bear research committees and authored reports about the species’ population in Canada. For decades, he has studied large carnivores, like wolves. He currently works as a senior scientist at the Raincoast Conservation Foundation, based in British Columbia.

Paquet initially thought grizzlies might make it back to the Cascades on their own, but reintroduction would certainly speed up the process, he said.

“It would be wonderful.”

‘On the side of the bears’

Historically, grizzly bears thrived in the North Cascades — an area spanning temperate rainforests on the west side to dry ponderosa pine forests in the east.

In the 1800s, an estimated 50,000 grizzlies roamed throughout western North America. By the 1930s, the population plummeted to fewer than 500, largely due to humans killing bears and destroying their habitat.

Today, scientists believe there are around 2,000 grizzlies in the Lower 48, with most of them in northwestern Montana.

The grizzly bear recovery zone covers portions of seven Washington counties, with most acreage in Chelan and Okanogan counties. Almost 57 percent of Snohomish County — including some of the most remote forest in the continental United States — sits in the recovery zone.

Rockport State Park is one of eight state parks in the North Cascades ecosystem.

There, groves of old growth Douglas fir trees stand at 250 feet tall under the shadow of Sauk Mountain. Patches of blossoming yellow skunk cabbage — often eaten by black bears — stand out in the evergreen landscape.

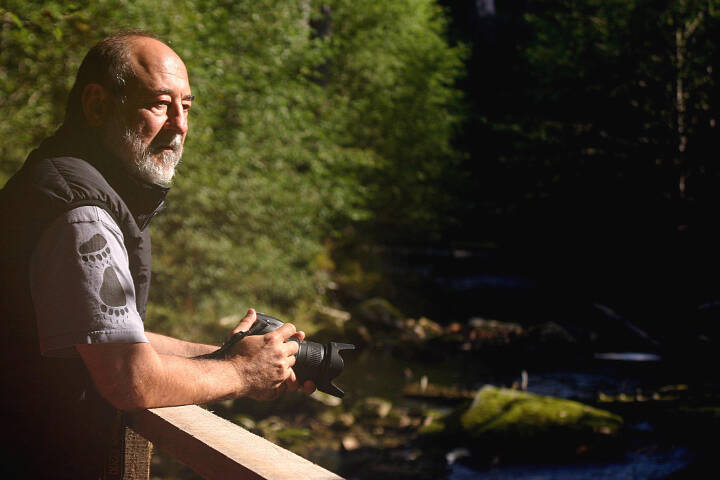

On a hike this week near Rockport, retired North Cascades National Park employee Russ Dalton recalled three encounters between 1995 and 2008 with a possible grizzly bear in the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest.

In every case, the bears looked larger than a typical black bear to Dalton. And twice, when he was accompanied by a ranger, they agreed it was a potential grizzly sighting. But Dalton never got close enough to inspect the tracks.

Dalton has 40 years of experience maintaining trails, restoring historic structures and working as an interpreter for the National Park Service and Forest Service. In his retirement, he spent five summers volunteering as a fire lookout in the Glacier Peak Wilderness, lovingly restoring the Miners Ridge lookout near Image Lake.

He has seen a black bear every year since 1963. Those encounters were almost always non-confrontational.

Ultimately, he supports the grizzly bear proposal, unless reintroduction efforts prove unsuccessful.

Dalton has sympathy for the grizzlies, who will suddenly wake up in an area they have never been before.

“It’s just a life of trauma for a long time,” he said. “I’m on the side of the bears. I just hate to see them have to go through that.”

‘Our way of life’

In November, over 100 locals packed the Darrington High School auditorium for a public comment session about the reintroduction plan. Many were vehemently opposed to grizzlies in what feels like their backyard.

Some feared how grizzlies might affect recreation. Shawn Yanity, a former chair of the Stillaguamish Tribe, said tribal members are worried about how bears may jeopardize already-threatened Chinook salmon populations.

“We need to sustain our culture,” Yanity said. “We need to sustain our way of life.”

Kevin Lenon, a Sauk-Suiattle tribal council member, expressed similar concerns in an email to The Herald this week.

“Once the grizzlies get into our spawning grounds, they are going to wipe out our runs,” he said.

He also worries the reintroduction plan will prevent tribal members from reaching their accustomed hunting and fishing grounds in the Cascades.

When people think of grizzly bears, they often imagine the bears standing in Alaskan streams, waiting to catch a fish, said Andrew LaValle, a spokesperson for U.S. Fish and Wildlife.

Those are coastal bears. The grizzlies in the North Cascades plan would be descendants of inland animals — omnivores with largely plant-based diets.

Grizzlies, though, are opportunistic foragers. If they see a salmon swimming in a stream or find a deteriorating animal carcass, they may eat it, LaValle said.

Park Service and Fish and Wildlife officials consulted the National Marine Fisheries Service while drafting the grizzly bear proposal, and the agency determined reintroduced grizzlies would likely not jeopardize any threatened salmon populations.

Bears spend four to five years teaching their young how to find food. And catching salmon is a learned behavior.

“If mom hasn’t had that experience, it’s less likely that the cubs are going to gain it,” said Bill Gaines, a wildlife ecologist and the executive director of the Washington Conservation Science Institute.

Between 2018 and 2020, hundreds of mountain goats were relocated from Olympic National Park to the Cascades, in part to support the depleting population in northern Washington — but also because they were deemed non-native to the Olympics.

Grizzlies might be successful in catching a goat on occasion, but they won’t dramatically alter the species’ population in the Cascades, said Jason Ransom, a National Park Service wildlife biologist.

“We don’t know exactly what proportion of their diet any given plant or animal may make up,” he said, “but we’d generally expect that the species that are more abundant would be consumed proportionally more often.”

Deer and ground squirrels, Ransom said, will probably make up the “relatively small percent” of meat that North Cascades grizzlies eat.

‘Where they can thrive’

Darrington Mayor Dan Rankin said he and others in town aren’t in favor of grizzly bear reintroduction because they’re concerned the animals will struggle to adapt to northern Washington.

“When we support them, we need to absolutely know that we not only have the environment to support them, but the environment where they can thrive in,” he said. “I don’t think the North Cascades is ready for that.”

Endangered and threatened species “need our nod,” Rankin said. But he doesn’t believe this plan constitutes environmental stewardship.

In the early 1990s, Gaines — the Washington wildlife ecologist — helped map habitat in the North Cascades to understand if grizzly recovery was feasible, before federal agencies committed to a plan.

He and other members of the team shared their findings with a panel of grizzly experts and determined the North Cascades ecosystem provided enough food, space and security to support grizzlies.

Two years ago, ecologists reassessed the area to ensure nothing significant had changed. And it hadn’t.

Washington’s moist environment creates a “rich diversity of plant resources and plant foods that the bears are going to be able to take advantage of,” Gaines said. “We know that also because we have a real healthy black bear population and there’s a lot of overlap in the food resources between the two species.”

It has taken over a decade to merely draft the Environmental Impact Statement on grizzly bear restoration in the North Cascades. Federal agencies began the process in 2014, but it was halted in 2020 by the Trump administration. In November 2022, the Park Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife reinitiated the plan.

This offers an extremely rare opportunity, Gaines said.

In a rapidly changing climate, restoring a key piece of the North Cascades’ historic ecosystem could provide a template for future conservation efforts.

Learning to coexist with grizzlies again, though, will undoubtedly take time. Locals haven’t truly lived with the animals for several decades. Federal agencies’ proposed plan tries to account for this.

“I think being really transparent with the restoration effort” is important, Gaines said. “Doing really good monitoring and giving people information about that monitoring, what the bears are doing, so we can learn together — kind of relive together — with these bears.”

In the event that federal agencies do decide to reintroduce grizzlies, Dalton said, “my hikes will not be the same.”

“I’m a vigilant hiker and camper because I so enjoy seeing wildlife, but there will be an added measure of Wildness and Wilderness on future trips into the North Cascades,” the former National Park Service worker wrote, in a typewritten statement of his feelings. “I will take that risk.”

Plan your adventures throughout the West Coast at westcoasttraveller.com and follow us on Facebook and Instagram @thewestcoasttraveller. And for the top West Coast Travel stories of the week delivered right to your inbox, sign up for our weekly Armchair Traveller newsletter!

Acclaimed carver creates culture-bridging welcome sign for Vancouver Island town

Acclaimed carver creates culture-bridging welcome sign for Vancouver Island town