(Editor’s Note: This piece was written before the COVID-19 crisis. Please adhere to the B.C. government’s travel guidelines and, in addition, check this website for information about current restrictions.)

This is Our Gift.

This is our gift to each other, our fellow Canadians and the world. …

We Nisga’a are leaders. Our art and culture tie us to this place. We have stories of wonder, tragedy, and triumph to tell.

Here, we will share them with the world.

— Partial quote from the Nisga’a Museum’s homepage (nisgaamuseum.ca)

To travel deep within the lands of the Nisga’a Nation is to reach out and try to understand the mysteries of ancient history. The vast Nass River Valley, a territory of towering tree-laden green mountains — some capped with snow — powerful, roiling rivers and streams, rugged and craggy lava beds, ocean, lakes and ponds, and a culture and a history all of its own.

It’s a place of death and great sadness, with thousands dying in Canada’s most recent volcanic eruption, nearly 300 years ago, and a place where residential school programs and other practices will never be forgotten.

Yet it is a place of great strength and abundance. The resiliency of the Nisga’a is well known. They struggled for more than a century before signing a land-claim settlement in 1998 that is the first formal comprehensive treaty in modern-day British Columbia.

There are four Nisga’a villages in the territory: New Aiyansh, which is now known as Gitlaxt’aamiks and houses the Nisga’a legislative assembly; Gitwinksihlkw, located on the Nass River; Gingolx, a coastal village on the Portland Inlet; and Laxgats’ap, located on the Nass River Estuary and home of the Nisga’a Museum.

But the building is much more than a museum. It’s a towering monument of wood and glass that thrusts skyward against the background of a lush green mountain.

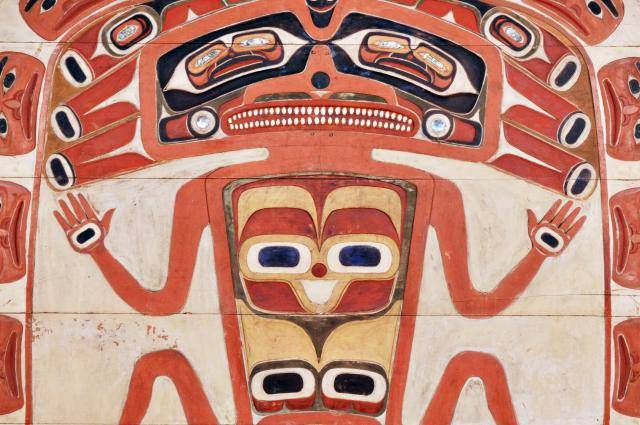

Also known as Hli Goothl Wilp-Adokshl Nisga’a (the Heart of Nisga’a House Crests), the Nisga’a museum’s design is inspired by the longhouse and the traditional Nisga’a feast dish and canoes.

It is simply stunning, with the 929-square-metre structure that houses an entire traditional building that displays the priceless Ancestors’ Collection, a collection of Nisga’a art and artifacts that were reaquired by the nation from museums in Ottawa and Victoria as part of the treaty deal.

The Ancestors’ Collection is the heart and soul of the museum, with its very entrance guarded by an awe-inspiring raven’s beak featuring human figures. The collection has beautifully carved masks, photos, traditional bentwood boxes, headdresses and other works of art.

As we walked through the museum, we read of how many Nisga’a artifacts were destroyed by missionaries who had come to the area, and how others were given away or sold to collectors and museums. We could have spent days at the museum, but after a few hours we were anxious to get back on the road and drive the remainder of the Nisga’a Nation auto tour. But before we left, we were offered a small amount of oolichan grease to eat.

For those of us who grew up in British Columbia, oolichan grease is legendary, not only for its strong taste and for its many methods of preparation, but for its nicknames: Saviour Fish and Candlefish.

Oolichan, for rivers that still have them, are a small and very oily member of the smelt family. They’re called Saviour Fish because they are the first fish after a long winter to begin migrating in B.C. On the Nass River, around the beginning of February, these fish begin to run.

Oolichan grease is made by boiling the fish until its oil floats to the top, and traditionally it was poured into wooden boxes for trade or stored for a food source throughout the year. It’s said that oolichan contains so much grease that they can be burned like candles when dried.

We were provided with a small amount of oolichan oil on a piece of bread, and we ate it with gratitude, in a magnificent setting, and vowed to ourselves that we would return one day.

Getting there:

There are regular flights to Terrace, which is a 100-kilometre drive from Nisga’a Village Gitlaxt’aamiks (formerly New Aiyansh). Travellers can also take a ferry through British Columbia’s spectacular Inside Passage. It runs from Port Hardy, on Vancouver Island, to Prince Rupert, and you can drive from there to Terrace and on to Gitlaxt’aamiks.

Essentials:

Nisga’a Territory is remote, and the Nisga’a government recommends that you travel with a full tank of fuel and bring food and bottled water as restaurants are limited. However, there is a full service gas station and grocery store in Nisga’a Village Gitlaxt’aamiks (formerly New Aiyansh). We enjoyed Chinese food at a restaurant in Gitlaxt’aamiks.

Accommodation:

Accommodation is limited, so arrangements must be made ahead of time. However, we camped at the excellent Nisga’a Memorial Lava Bed Park Visitor Centre Campground. The Nisga’a Lisims Government runs an excellent website. Here’s the link to accommodation and other visitor tips.

Red Deer: It would take you days to hike this city’s trail system

Red Deer: It would take you days to hike this city’s trail system