Without a doubt, Shawnigan Lake’s biggest piece of history is the Kinsol Trestle — literally — and yet it almost didn’t make it to the present day.

Also dubbed the Koksilah River Trestle, this wooden railway trestle on southern Vancouver Island, north of Shawnigan Lake, was built as a crossing over the salmon-bearing Koksilah River.

The breathtaking bridge stands 144 feet high, and 617 feet long, earning itself the title of the largest wooden trestle in the Commonwealth and one of the tallest towering timber trestles worldwide. It was built as part of a plan to connect Victoria to Nootka Sound, while passing through Cowichan Lake and Port Alberni.

One of the most impressive things about the trestle’s rich history is that it was originally built by a mere 55 local men who were not bridge-builders by trade, but rather farmers and general labourers.

“These guys were literally out in the middle of nowhere with equipment that was nothing like we have nowadays,” says Shawnigan Lake Historical Society Executive Director Lori Treloar. “They were just out there plugging away, and of course there’s not one timber on the trestle that could have been carried by one person. Now, skip ahead to the rehabilitation, where there were over 100 guys, five stationary cranes, and the list of equipment that they had at their disposal goes on and on, compared to what the initial 55-man crew had.”

Treloar who grew up in a cottage on Shawnigan Lake, says she had no idea about the Kinsol Trestle until she began working with the Shawnigan Lake Museum in the early 2000s. The sight of it blew her away, and she has been exuberantly steering people there ever since.

“It’s gobsmackingly gorgeous,” Treloar says. “There are so few large heritage structures like that around anymore, so I think we benefit, and it’s why people are so interested in it. It’s really a marvel, especially when you think about the small number of local general labourers who built it.”

The original trestle was built during a time when forestry had shot up on Vancouver Island, and a more efficient way to transport the region’s huge, old-growth timber was needed. Surveying of the Cowichan Subdivision began in 1910.

The much-needed line got on track in 1911, started by the Canadian Northern Pacific Railway (CNoPR). The Canadian Western Lumber Company – the largest lumber company in the world at that time – supplied the funds, while local farmers and loggers supplied the blood, sweat and tears working on the trestle.

However, under CNoPR’s watch, the line only reached as far as Youbou, before construction was terminated.

“The feds forcibly took over the debt-ridden Canadian Northern Pacific Railway and incorporated it, as well as the Island extension, into the Canadian National Railway,” Treloar says. “At that time, only eight miles of steel had been laid from Victoria.”

The total cost to build the original trestle was $26,000 and it was completed in February 1920 as part of the ‘Galloping Goose’ rail line which carried not only passengers but also freight – primarily timber and other forest products. By April that year, steel crossed the canyon, and Treloar says several logging companies chose to establish their mills near the trestle.

It was christened the Kinsol Trestle after the nearby Kinsol Station, which took its namesake from a mining venture in the area that was given the grandiose name of ‘King Solomon Mines’ which at the time used three rail cars to mine copper and silver between 1924 and 1927 and operated just north of the trestle.

Flooding and large trees being hurtled into the structure during the early 1930s led to reconstruction in 1934, adding Howe Trusses to the bottom of the trestle; upper Howe trusses remained in place until 1936, then were removed and filled in with bents.

The thick timber planks had Roman numerals hand-carved into them to show where they belonged on the trestle – quite the task in itself. After 1958, repairs remained sporadic and minimal.

The final ride.

The last locomotive to ride the rails across the Kinsol Trestle was in 1979. That same year both organizations and individuals petitioned the provincial government to have it designated as a heritage structure.

With legal rights left to B.C.’s Ministry of Transportation, trestle care was abandoned, once higher-ups decided the trestle posed a threat of environmental concern, and a potential danger to the public.

After the last ride, came one final freight. Canada’s tallest wooden flagpole, which was built from one of the fir trees from the Shawnigan area, was part of the last load to cross the trestle. Being made of wood it eventually yielded to rot and was replaced by steel. (Treloar says the expanded Shawnigan Lake Museum will host a related mini exhibit later this fall.)

The rails were removed in the early 1980s, marking the beginning of the structure’s deterioration, furthered by vandalism, encroaching vegetation and eventually fire.

In June of 1988, the first of two deliberately set fires left an eight-metre gap on top of the trestle.

A decade later firefighters responded to a second fire where they found flames burning through timbers on the upper deck which were sparking fires below. Shawnigan Lake Fire Chief Sanders called in the Martin Mars Water Bomber from Port Alberni which made four passes and dropped a mixture of water with foam. This did not extinguish the fire but gave firefighters more time as helicopters swung buckets of water on timbers underneath.

“To see the Martin Mars fill up on our lake, was incredible because it’s not a big lake,” Treloar says. “Then to witness it dropping water over the Kinsol Trestle to save it was another magical thing to see.”

Following the fire, the Ministry removed the first few bents from the north and south sides to restrict access.

Community rallies

Community members who also saw the magic of this structure constructed from old-growth Douglas fir timbers, with a rare seven-degree curve, were soon up in arms, and putting their best foot forward to save it. A handful of local groups began putting their heads together for fundraising efforts to preserve the Kinsol Trestle for not only its historic value, but also for what it could do for tourism in the Cowichan Valley.

“From my point of view, one of the most important things is that the community saved the trestle when the government wanted to tear it down,” Treloar says. “The community agitated until the government finally broke down, and now through tourism roughly 300,000 people go out there every year, so the government was clearly wrong on that.

“It’s not just people from Shawnigan that go, it attracts visitors from all over the world. It’s an amazing story of survival that countless people were involved in.”

In April 2006, the B.C. Ministry of Transportation announced that the trestle was coming down and it was transferring $1.5 million to the Cowichan Valley Regional District to dismantle it in an effort to mitigate potential liability issues. The CVRD later held a special meeting on June 7, 2007 and decided it would not only be spared but resurrected. During this initial first meeting with the CVRD, Macdonald & Lawrence Timber Framing Ltd., a firm that specialized in building conservation, proposed a strategy that would see the bridge fully restored for pedestrian use as part of the Trans-Canada Trail network.

“They picked the right people to do it,” Treloar says. “MacDonald and Lawrence were hired to do it because they had a real passion for the project, the same could be said for everyone who worked on it, including the community members who came together to save it.”

By November that year, a thorough inspection of the trestle found that 80 per cent of the major timbers on the trestle were still sound, making the dream of restoration a reality.

Rehabilitation doesn’t come cheap

In 2010, the estimated cost to rehabilitate the trestle was $7.5 million. With many donations from community members and organizations coming in, more than $7 million was raised. Many can argue that it was money worth spending, leaving valley residents and visitors with one of the few accessible and visible reminders of the early mining and logging industries that once thrived on the Island.

The Kinsol Trestle, now a part of both the Trans-Canada and Vancouver Island Trails, reopened on July 28, 2011, staying true to its heritage with little nods such as returning telegraph poles to their original places.

Amazingly, out of the original 44 bents, only 17 had to be replaced in the eventual refurbishment, and today it’s nearly impossible to distinguish between the old and the new.

“I could confidently say that 95 per cent of those living in Shawingan Lake would recommend to a friend or a visitor that the trestle is one of the first things that they should see,” Treloar says. “There’s just something magical about that bridge.”

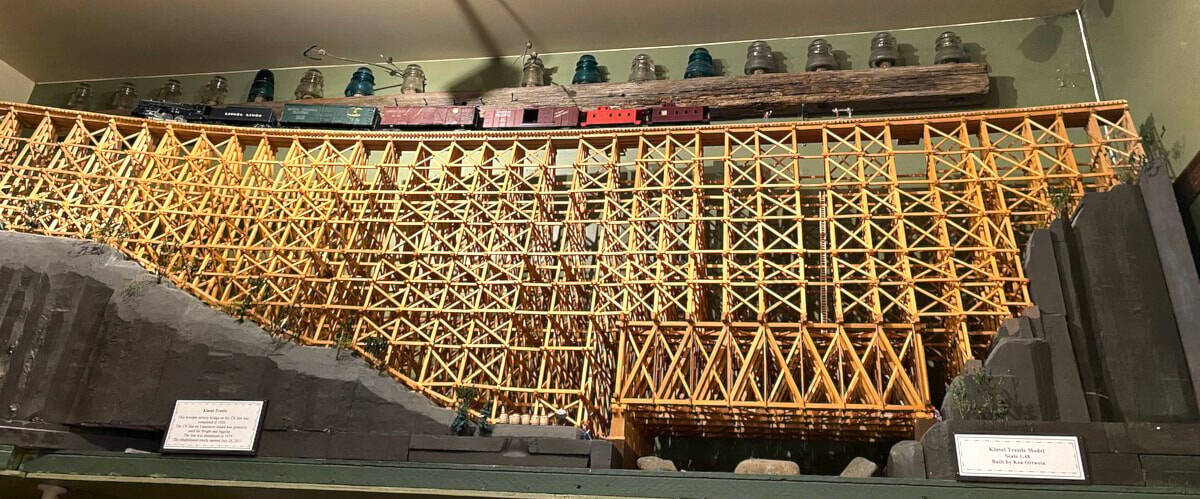

Treloar says tourists will often visit the museum with excitement after seeing the trestle for the first time. Beyond a wealth of information, museum visitors can also take in old photographs, copies of the original plans and some must-see models.

Visitors to the expanded museum that will open later this fall will be treated to an even more impactful model of the trestle built by one of the timber framers that worked on the bridge’s rehabilitation. Treloar is passionate about leading guided trestle tours and when escorting large groups only asks for a mere donation. Book your guided tour today by contacting Treloar directly at lori@shawniganlakemuseum.com.

“I love to inspire people through these tours. The story is so big, it’s almost unbelievable that we have the trestle in the condition that we do today,” said Treloar. “When you stand at the bottom of the trestle and look up, one would be hard pressed to find anything as beautiful.

“I hope all who visit it feel a sense of respect for it, to those who built it, and to the community who saved it from demolition. It’s a must see!”

If you go:

- The Kinsol Trestle is open year-round, from dawn to dusk, with public vehicle access to the Kinsol is from Shawnigan Lake through to the south end of the trestle.

- Plan your visit at cvrd.ca/1379/Kinsol-Trestle

Plan your adventures throughout the West Coast at westcoasttraveller.com and follow us on Facebook and Instagram @thewestcoasttraveller. And for the top West Coast Travel stories of the week delivered right to your inbox, sign up for our weekly Armchair Traveller newsletter!

Victoria waters a picturesque paradise for freedivers

Victoria waters a picturesque paradise for freedivers